A grisly start to the 20th century

Burlington Retro reaches beyond Burlington when the story is interesting enough. This is one of those stories, retold by Burlington Retro based on Lowell Sun and Boston Globe archives.

Chelmsford, MA, June 9, 1901 — Sunday afternoon, a nosy little calf smelled something funny and meandered away from the town farm. Superintendent Elmer Hildreth and farmhand William Balser set out to find it. Near an old logging road, they came to a woodpile. Maybe the calf was hiding behind it. As they approached the pile, however, they had to pause. Something smelled like rotting meat. But what? And where was it? Then they noticed human limbs near the bottom of the pile. They belonged to a partially clothed woman, lying face down. Her head was missing. The men staggered away and notified Selectman John E. Warren and Constable George Wright, who then notified Lowell Police.

Doctor J.V. Meigs, the medical examiner, said she was about 30 years old, 5’4″, about 140 lbs. Severe blows to the back of the neck, from a sharp object, had separated her head while she was face down.

Her decomposition suggested she had died at least a month ago, yet she was easily visible from a nearby wood hauling route. With logging still in season, why hadn’t anyone noticed her until now? Surely she had been killed elsewhere and dumped here. No women visited this area besides wives of the woodchoppers, but this woman was wearing brown stockings, a heavy flannel undershirt, a heavy cotton-ribbed, fleece-lined undershirt, brand-name underwear and corsets in perfect condition. Awfully fancy for a woodchopper’s wife. Besides, the woodchoppers’ supervisor noted that his men knew the area really well and could have hidden a body much better than this.

Identifying a dead body is much easier when it has a head. Authorities needed to find it pronto. A generous Chelmsford resident offered a $25 reward for the missing head, in an effort to prompt neighbors to form a posse. Another resident suggested using hounds to track a scent, perhaps after letting them sniff the victim’s clothing. Unfortunately, the undertaker had burned the clothing, confident it would serve no further purpose, a move that infuriated local police. Nothing remained except her inner and outer corset — garments used to suck in the waistline.

The headhunt lasted only one day. A private detective found it in a bag, submerged in a nearby stream, weighed down by a couple of rocks tied to the bag. The detective took the head to his barn, where a huge crowd of reporters and onlookers gathered to view it and the crime scene. This is before yellow police tape and meticulous crime scene forensics.

A Lawrence woman asked to view the remains, fearing it might be her aunt Margaret, who worked in the Lowell and Chelmsford mills. Her aunt had gone conspicuously silent after marrying and quickly separating from a 37-year-old French Canadian named Joseph Wilfred Blondin. The couple’s courtship was only a few months, and the marriage quickly deteriorated when she refused to move back to Canada with her husband. The couple lived at 43 Green Street in the old West End of Boston.

The victim’s head was too decomposed for easy identification, despite earrings and false teeth. But the Lawrence woman recognized those corsets right away: “It’s my aunt!”

The police told the Sun to stay quiet about the identification, to give them time to close in on her estranged husband, Joseph Blondin. But the Sun could not resist the chance to beat other newspapers to the story:

By the time police could raid Blondin’s apartment at 43 Green Street, the bird had flown. “If you newspaper cusses had kept out of this thing for a few hours longer, we would have caught him,” said officer Dunham from the state police. “Blondin was in Boston this morning but left suddenly, presumably to go to Canada.”

The newspaper returned fire, writing that the officer who witnessed the positive identification should have immediately notified Boston police for a quick arrest, but instead wanted the “glory of the arrest” for himself. So he went to bed that night with the information locked in his “manly bosom,” planning to be the hero the next day by nabbing Blondin himself. The paper said it had no obligation to assist that self-aggrandizing plot.

Nowadays, police use technology to make things very difficult for fugitives: instant bulletins to other agencies, websites, global positioning satellites, cell phone tracking, social media, drones and even facial recognition technology. Not so in 1901. The manhunt for Blondin became big news across the US and Canada. Sightings came in from literally everywhere. The chase became futile.

June 17 — People in Kenwood alarmed at a man skulking behind trees in that vicinity. Believed to be Blondin. Armenian in Lynn arrested for Blondin. Some people confident that Blondin is in Tyngsboro.

June 17 — State officer Neal comes to Lowell. Blondin thought to be in Springfield, New Haven and Portland.

June 18 — Officer Dunham applies for a warrant for Blondin’s arrest. Blondin’s trunk and bicycle found in New York and New York police on the alert. Facsimile of a letter written by Blondin and signed “Joe Morrau” reproduced by the Sun.

June 20 — Police lose track of Blondin. Man in Chicago arrested for the fugitive. Blood-smeared articles found in Blondin’s trunk in Boston. Blondin traced to Greenwich, Connecticut. His picture sent broadcast.

June 21 — Blondin believed to be in Lawrence. He was seen in Stamford, Connecticut. Man hiding In Quebec woods which answers Blondin’s description.

June 22 — Boston officials take charge of the crime. Circulars issued by officials. Opinion divided as to the scene of the crime.

June 24 — Inquest on the death of Mrs. Blondin. Mr. Blondin reported arrested in Brushton, New York. Police searching for another of Blondin’s trunks.

June 25 — Blondin’s rooms at 43 Green Street in Boston searched. Police satisfied that the murder was committed in Boston. Evidence that Blondin pawned his wife’s clothing.

June 26 — Blondin seen at Wallingford, Connecticut.

June 27 — Suspected murderer at Fall River.

June 28 — State officers search in Chelmsford for missing trunk.

June 29 — Young man at Sharon Heights says he is Blondin.

July 1 — Two men positive they saw Blondin in Chelmsford in the woods. He is armed with knives and guns and has his bicycle. Police searching the woods.

July 2 — Blondin seen at Hudson.

July 3 — Blondin is seen at St. Remy, Quebec.

July 6 — Blondin seen in Quebec, Providence and New York. He is clean shaven and wears a full beard.

July 8 — Blondin hiding in Quebec and eating fish and fowl.

July 9 — Blondin captured at Grahamsville and awaits the arrival of Boston officers.

July 10 — Another Blondin arrested in Middletown, NY.

July 17 — Police at Barrington, Nova Scotia believe they have captured the real Blondin. He is also seen in the woods near Milford, NH.

July 18 — Blondin seen in Belvidere. Blondin captured in Mt. Upton, NY.

July 19 — All suspects released.

July 29 — Officer at Matane Lights, Quebec, sure he has Blondin. He is mistaken.

July 27 — Dispatch from Woodstock, New Brunswick says Blondin was killed by an express train.

Aug. 1 — A trunk and barrel of clothing sent from NY to Bedford investigated by state police officers.

Aug. 3 — State officers enjoying vacation in wilds of Quebec are chasing Blondin, assisted by men all armed with guns. Boston newspapermen are spending their vacation with the Boston police in Quebec woods, chasing Blondin all the while.

Aug. 7 — Blondin seen in Quebec woods several times. Arrangements made to smoke or burn Blondin out of the woods.

Aug. 9 — Telegraph operator at Little Metis, Quebec, saw a man with bowed legs, but it was his uncle.

August and September — Blondin is seen in many places in Canada. Officers and scores of people have seen Blondin in the woods of Quebec. People claim to recognize him. Sleuths have not caught up with him.

In February, 1902, after five months without a single Blondin sighting, a man walked into New York City police headquarters at 300 Mulberry Street to apply for an engineer license to operate a steam boiler. On the wall was a Boston police photo of Blondin and a handwriting sample. As the applicant stood gazing at the photo, an alert patrolman noticed a strong resemblance between the applicant and the man in the photo. New York police quietly sent a telegram to Boston police and set a trap. The man was told to come back for the engineer’s examination Feb. 25, 1902 at 11 a.m.

When he showed up, he was surprised to see Charles Patterson from Boston, his former neighbor. Boston police had quietly brought him along as part of the setup. As soon as Blondin walked in, Patterson surprised him by saying, “Well hello, Blondin.” Of course, Blondin reflexively nodded and said, “How do you do.” Police then arrested him before he had time to resist.

And yet, for about a half hour, he still denied he was Blondin. He claimed he was Joseph Bernard. Finally, Patterson yelled at him: “What use is your denying it? When you came in here I spoke to you as Blondin, and you answered. I knew you when you lived at 24 Staniford Street, Boston, and I know you now. You are the same man I knew in Boston as Wilfred Blondin.” The man shuffled around for a while and finally said, quietly, “Yes, many name is Wilfred Blondin, but I did not commit any crime.”

This was 64 years before Miranda rights, so he did not have the right to remain silent or “lawyer up” right away. He tried to talk his way out of the handcuffs:

“All I know is I went with her the last Saturday in April to South Station to see her off for Providence. I bought a ticket for her, and while I was in the box, she went away. When I came out, I could not find her, and I never knew where she went.” When she never returned, he assumed she had left him for good, he said, so he donated her clothing to charity and went on some cruises overseas. He returned and got various jobs around New York. Then came the headline about her body being found in Chelmsford. “I ran away when I saw that she had been killed, when I read it in the papers. I was frightened because I could not bring anybody to prove that I had lost her in South Station. I was terribly frightened, for I knew it would be hard for me to show the truth.”

As the hours passed, he came up with another story, this time while sobbing. “There was a man who was been writing letters to my wife. I know of two that she got. She would never let me see them, and she would not tell me who they were from. When I was going to hunt for them in the room, she made me get out. He may have killed her.”

Would a jury buy this? It was time to seek an indictment — but where? There was no evidence of a crime at squeaky-clean 43 Green Street, yet nobody believed the woman was killed where she was found in Chelmsford either. Finally a grand jury convened in Middlesex County to weigh an indictment, a necessary step before a murder trial. While awaiting the start of courtroom proceedings, police continued to badger Blondin, this time about love letters they found in his belongings. The letters showed that soon after his wife vanished, he had gone on a couple of ocean cruises with another woman. He now characterized her as merely “a friend.”

Blondin’s landlady said he and his now-dead wife were an odd couple, rarely leaving the apartment. He replaced the door lock immediately after moving in and was very vigilant.

Then from out of the shadows in Canada came Blondin’s first wife — reluctantly. She’d been living under an assumed name and was basically dragged out of the shadows by Boston police. She agreed to testify against him, even though she was not eager to recount her nasty marriage to him when she was 18 and he was 26. Incidentally, the couple had not divorced, making Blondin a bigamist for marrying again, but that was the least of his problems right now.

She told the Associated Press that Blondin treated her badly and the couple’s three children even worse. All had died after severe neglect. “When my little girl died,” she told the AP, “I sent for my husband, who was then working at the Richelieu Hotel, but he would not come. I begged and prayed him by messenger to come, but it was only after some neighbors brought their influence to bear upon him that he would come to see his little child as she was laid out on the bare floor. Then all he did was to say, ‘Why did you not let me remain where I was? I am tired enough already.’

“When I heard that the woman with whom he was living had been murdered, I said to myself, ‘He did it.’ I myself was always in fear of being murdered, and even now I am as much afraid of him as I was in the past. I dream about him almost every night, and I have the most horrible dreams. The other night I dreamt that I was to take part in his execution on the scaffold, but, strange to say, he disappeared.”

On March 10, 1902, a grand jury indicted Blondin on four murder-related counts. That was easy, but would the trial be so easy? So far, there was no hard evidence linking Blondin to the crime. Nine months later, it was time for jury selection. Blondin appeared in court in a black suit with blue tie and personally grilled the potential jurors to weed out any biases. That was the judge’s order — that Blondin himself question the juror pool.

Here are the judge, prosecutor and defense attorney.

And here are seven of the Blondin jurors. Could they sniff out the truth despite those mustaches?

The trial began Dec. 1, 1902. In its opening statement, the prosecution said Blondin strangled his wife April 27 at their Green Street apartment and transported the body to Chelmsford April 30. Then he chopped off her head and tossed it into the river nearby. Motive? Unknown. Maybe just explosive anger, or jealousy, or maybe money, since Mrs. Blondin had withdrawn all of her money just prior. Why dispose in Chelmsford? He knew the area because he had worked for a local farmer named Osterhaute. Witnesses? Someone claimed that a man matching Blondin’s description told him his wife was dead. A ticket agent at South Station says he saw Blondin with a huge, locked box, presumably containing the dead woman. Blondin was very agitated, confused about simple money transactions and sweating profusely. And his time on the lam? When the Sun published the story about the body being identified, he hastily fled to New York and hid in the belly of a transatlantic steamboat, informally working as a fire stoker until he reemerged at the New York police station.

Here are the key trial exhibits:

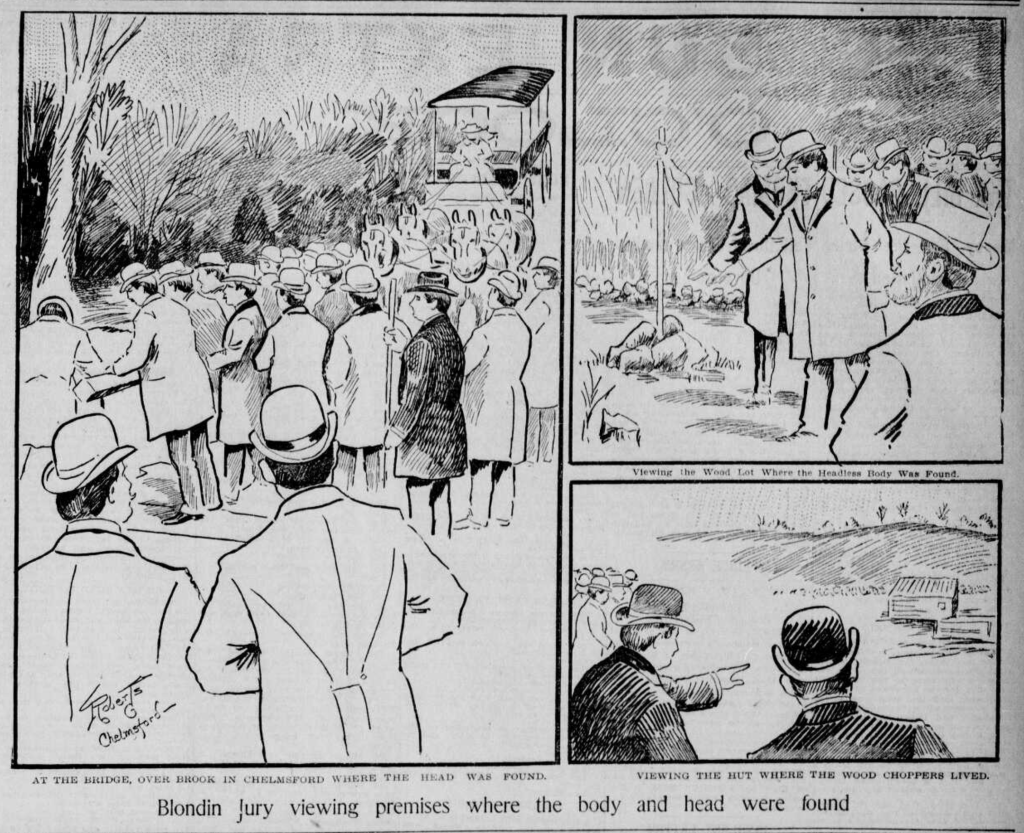

The next day, jurors went on a field trip, literally, to view the area where the body was found.

Then came a star witness, Mary J. Casey of Lawrence, the woman who had identified the remains of her aunt. The Boston Globe painted a colorful account of the courtroom encounter between Blondin and Casey: “The moment she had been sworn, Blondin straightened himself up and at once threw off the languid air which he had maintained previously during the trial. Miss Casey, on her part, faced the prisoner with determination written on every line of her face. It speedily became apparent that the feeling between the defendant and the witness was anything but kindly. Blondin flushed to the roots of his hair.”

Next on the witness stand: Blondin’s Canadian wife. “Mrs. Lucia Blondin managed to create a decided sensation. It was not so much what she said but the way she appeared. If a handsomer woman than Mrs. Blondin has strayed into the courts at this session, it is not in the memory of any of the court attendees.” Prosecutors asked almost nothing about her relationship with Blondin, probably at her request. Her appearance simply drove the point home that Blondin was already married when he married the victim. “Blondin’s eyes never left her while she was on the stand. He persistently attempted to catch her eye and had the brightest smile ready for her, but she was careful not to look his way, so his effort was wasted. When Mrs. BLondin stepped from the stand, she walked directly toward Blondin in the cage. He was waiting for her, and his face was literally wreathed in smiles as she approached. Those looking for a scene were disappointed. Try his hardest, Blondin could not catch his wife’s eyes. She made a particular point of keeping her eyes in another direction, and the prisoner’s face ached in disappointment as she swept out of the room.”

After calling a porter who handled Blondin’s huge locked box, and a witness who saw a man arrive by coach near the Chelmsford woodchopping area, the prosecution rested. The defense tried to assassinate the character of every witness. The baggage handler had a drinking problem. Blondin’s Canadian wife was living with another man out of wedlock. The court heard 125 witnesses in total. Finally, on December 12, 1902, the case went to the jury.

The case was entirely circumstantial, but then again, hard evidence wasn’t easy to find in 1902. No weapons analysis, no DNA testing, no ultraviolet light techniques to ferret out blood spatter, no surveillance cameras to confirm whereabouts. Just a lot of incriminating tidbits and, most importantly, sentiment toward the accused and assessment of his character. The two star witnesses, the women, had poisoned the jury’s image toward Blondin without any incriminating words. The condemning stare of the first one, and the condemning blind spot of the second one, had silently said it all.

He did not even flinch as he was sentenced to life in prison. Although he escaped the death penalty, he died in prison 17 years into his sentence. Cause of death? Unknown. He had suffered from neuralgia of the heart but apparently recovered. His father, a wealthy Canadian lumberman, had repeatedly tried to secure a pardon for his son. Meanwhile, his son was making a lot of money in prison by creating and selling walking canes. During World War I, he bought $200 in Liberty bonds and War Savings stamps. During the influenza epidemic, he helped the prison doctor care for inmates. So it seems he thrived in a controlled world populated by men but failed miserably among women.

The pursuit and prosecution of Joseph Wilfred Blondin was the most complex and expensive in New England history at the time.

Categories

Read this mystery story word for word with morning coffee! Good…he didn’t escape! A long time ago but I am familiar with the area in Chelmsford.

Interesting to say the least!

Fantastic summary for a remarkable case.

As an interesting aside, the lead defense lawyer, John Henry Morrison got sick from the stress of this highly publicized case at start of murder trial, and his younger assistant, James Owens stepped up to the plate on short notice. Morrison never practiced law again, and died 2 years later.